An introduction to child mental health theories

In recent years there has been an unprecedented rise in the number of children and young people with mental health issues, accelerating further in the wake of Covid-19. This result is a challenging situation for schools, but one in which teachers are in a prime position to make a difference.

We’re going to outline some of the key theories that relate to mental health and apply them to school settings, to help teachers better understand the child mental health situations they see.

We’ll start with a quick look at what we mean when we talk about mental health. Being mentally healthy means being productive, having fulfilling relationships, being able to adapt to change and cope with adversity. It’s not about being happy or sad, it’s about being able to cope with everyday life.

What is mental health?

Mental health includes our emotional, psychological, and social well-being. It affects how we think, feel, and act. It goes a long way to determining how we handle stress, interact with others, and make choices.

For some children, the stresses they face can sadly cause mental health issues such as anxiety, eating disorders, depression, or self-harm. There is no clear reason why some children develop mental health issues while others don’t but being exposed to traumatic experiences can make it more likely. These experiences might include abuse, bullying, death of a loved one, family breaking up, long-term illness, moving home, poverty or violence in the home.

Mental health conditions and trauma act as a barrier to learning. Teachers who understand even basic mental health theory and practice can help to support their students. Indeed, some schools are now ‘trauma-informed schools’, which means they train teachers and other staff to recognise and respond to mental health conditions and trauma in children and young people.

Always start with 'Why?'

It is not what a child does that matters, but why they do it. Each child is an individual, so to support them, you need to get to know them.

Carina Robertson, who lectures in psychology at Plymouth Marjon University explains: “The key thing to remember when focusing on a child’s mental health is that everything you do needs to be child-centred. The child is behaving this way for a reason. You want to look beyond what the child does and figure out why they’re doing it. Once you understand why they are behaving as they are, you can then approach the behaviour in a compassionate way and not exacerbate the child’s difficult feelings.”

In trying to establish why a child is behaving in a certain way, the smallest of things can be a signal. For example, say a child arrives 10 minutes late and wearing the wrong socks; if this is unusual for them, speak to them gently, asking what has been going on this morning? If they are stressed, then reminding them of the school’s attendance and uniform policies might make things feel worse for the child, especially if things are amiss for reasons outside of their control. Always take a moment to understand why things are as they are. You might like to find out more about how to support children with mental health conditions. But now back to the theory…

Attachment theory

Attachment theory explains how a child interacts with the adults looking after them. It describes how the parent-child relationship emerges and influences the child’s subsequent development.

If a child has a healthy attachment this means the child is confident that the adults in their life will respond to their needs, for example when they are hungry, tired, or worried. In turn, this gives the child confidence, a secure foundation from which to explore the world, and a good sense of self-esteem. Healthy attachment helps the child grow up to be a happy and functioning adult, better able to manage their own feelings and better able to relate to others.

Conversely, if a child can’t rely on their carers to look after them because they are inconsistent, insensitive, or unreliable, then that has damaging consequences for the adult that child will become. For example, the child may become very anxious when they can’t predict how the adults around them will act; or they’ll give up trying to get their basic needs met because they have too often been ignored. Their development may be delayed in terms of learning, emotional regulation, and self-control.

Some of the things you’re already doing in your teaching practice, like providing a structured environment and keeping calm and consistent, are especially supportive of attachment disordered children. You help them too by maintaining your professional boundaries - being their teacher, not their friend. If you can develop a trusting relationship with the child, this will help them even when they move on from your class; as they’ll feel more confident about doing it again.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

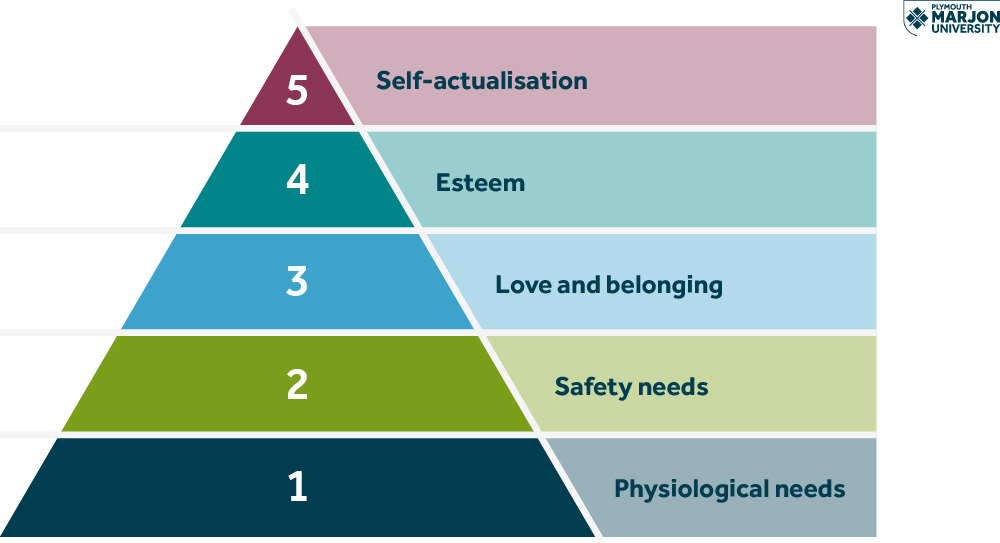

Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs is a motivational theory in psychology, it suggests that before individuals can meet their full potential, they need to satisfy a series of needs. The needs lower down in the hierarchy must be met before they can satisfy the higher levels of need. It reminds us that students are less able to perform to their full potential if their basic needs are not being met.

At the base of the hierarchy are physiological needs, these include fresh air, food, water, sleep, and warmth. If the student has these needs met, then next are their safety needs, they need to feel safe and secure at home, in school and wherever else they go. The third need is love and belonging – this is all about a sense of belonging to a group and building strong relationships. Then comes esteem, this is the need to feel good about yourself which in school relates to things like whether they are respected by their classmates, and what feedback and praise they are getting from their teachers.

Maslow's fifth and final stage is self-actualization. This is about realising their full potential, feeling self-fulfilled and pursuing personal growth, or as Maslow himself put it way back in 1943, they have “the desire to accomplish everything that one can, to become the most that one can be”.

Breaking the hierarchy down into the five steps is a helpful way of thinking about whether all the child’s needs are being met in the classroom. For example, starting out with physiological needs might include things like providing all students with access to water or to healthy snacks to maintain their concentration and energy. It could also include providing a nap room or rest space for overtired students, or ensuring they have coats, sun cream, welly boots, or whatever they need for the climate. In terms of safety, we might look at bullying, and for love and belonging, we can look at helping the child to build friendships, consider our relationship (student-teacher) or the ways in which we do group work.

Moving on to esteem, are we regularly giving them positive feedback? Are their peers doing the same? Does the child have an encouraging and realistic view of their own strengths? And finally, in terms of self-actualisation, are you setting the expectation that students always perform at their best but without overly pressuring them so that this turns into stress. Ask the child how it’s going and let their feedback guide you.

Flipping the lid

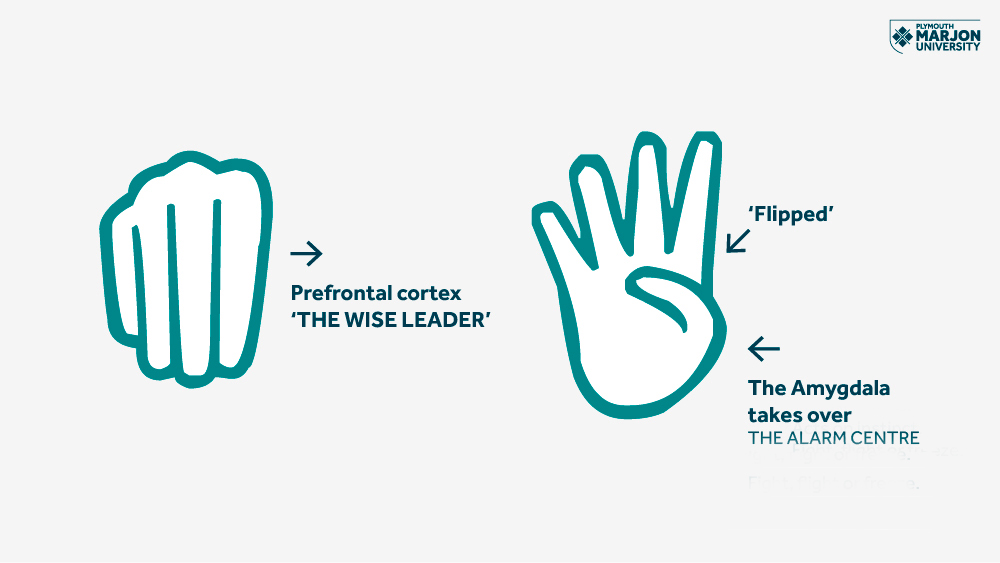

Back to Carina Robertson to introduce us to a concept known as ‘flipping the lid’: “Flipping the lid helps us to visualise, at a very simple level, what happens in the brain when emotions explode. Think of the calm brain as a clenched fist. When emotions take over the fingers of the ‘hand brain’ flip up. This represents the child being triggered and when this happens their central cortex, that’s the bit which runs the higher brain functions, disconnects from the other parts of the brain. The result is that the emotional parts of the brain (the amygdala) are left running the show”.

For more info see this talk on the flipping the lid concept by its originator, Dr Dan Siegel.

It’s not that emotional reactions are a bad thing, not at all. Anxiety and fear are natural and necessary emotions. They are experienced by everyone and are helpful in protecting us in the face of danger. But they become unhelpful if they are triggered when there is no danger, for example by an internal thought or by the external situation. For example, anxiety may be activated when a student is called to speak in class, told off by teachers, or in conflict with other children.

Carina explains why teachers can use humour to connect with an anxious child: “Using humour to help a child to regulate their anxiety is one of the most powerful tools in a teacher’s repertoire. Humour activates the brain’s dopamine reward system, and dopamine is known as the feelgood chemical because it does amazing things like reduce anxiety, fear, and sadness, and increase energy and self-esteem”.

Think back to the example above about the child with the wrong socks. The teacher could use humour to explore the situation in a sensitive way, saying something like: “I notice you've got odd socks on. What's going on here? Did you forget to put the lights on this morning?”. Now in itself, the act of wearing the wrong socks doesn’t matter. But if you think something more serious is happening then using humour to explore the seemingly small things may give you new insights into what is going on in the child’s life.

Playfulness, Acceptance, Empathy and Curiosity - PACE

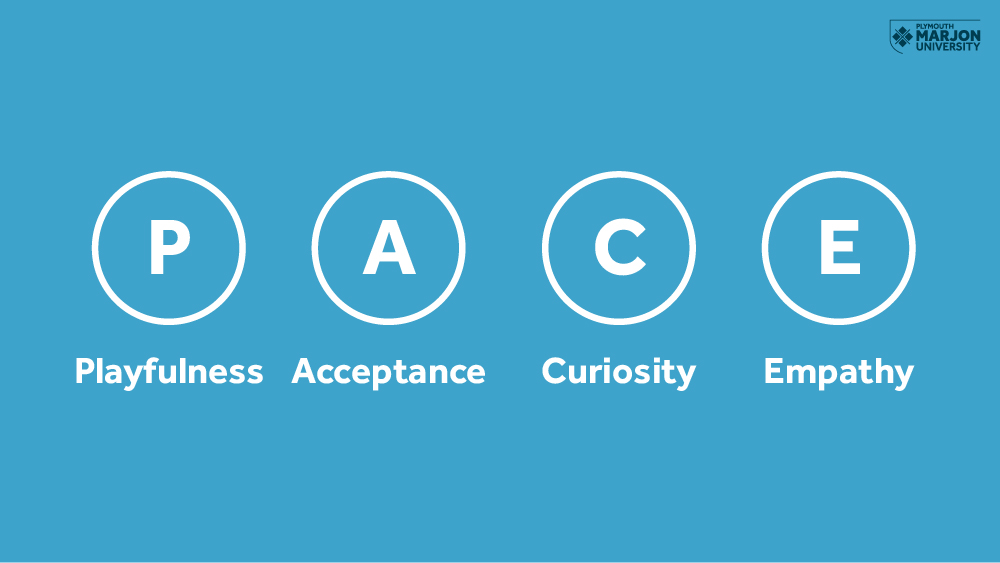

PACE is a way of thinking and communicating that aims to make the child feel safe. Put forward by Golding and Hughes in 2012, PACE stands for Playfulness, Acceptance, Empathy and Curiosity. It was inspired by the ways parents connect with very young children.

PACE helps adults to slow down their reactions, tune into what the child or young person is experiencing in the moment and guide them through their heightened emotions and thoughts. It also helps develop a sense of connectedness and understanding between the child and the adult.

Playfulness

You want to create a light and playful atmosphere and use a light tone of voice. This could be through activities that involve both the child and the adult.

This is what playfulness might sound like: “Gosh, look at the paints Joe, it looks like Nibbles (the class hamster) has been running around the table knocking them all over. Are you OK? You look really sad. Why don’t we see what we can do about it.”

Acceptance

Accept that whatever the child (or you) is feeling right now is OK. Show you understand, say something like: “I’m sorry you think X, that must feel awful, no wonder you did Y”. You can still tell a student to stop bad behaviour, whilst showing an understanding of it.

This is what acceptance might sound like: “Oh Joe, it feels annoying when things go wrong like your picture getting ripped everywhere, doesn’t it? I get so upset when my work gets spoiled.”

Curiosity

Ask lots of questions of them to know more about them. What do you think that was about?” or “I wonder what…? This way you can avoid jumping to inaccurate conclusions.

This is what curiosity might sound like: “Hey Joe, your art is usually so amazing, what happened today? Is there something distracting you from your work today, is your mum poorly again or are you feeling upset about something?”

Empathy

Put yourself in the child’s shoes and try to feel what they must be feeling. Being empathic is not about reassuring the child, simply being with them in the moment and helping them to carry their big emotions. Show that you know this is difficult for them and they are not alone.

This is what empathy might sound like:“Oh Joe, you got angry while you were painting. You looked really annoyed, it doesn’t feel good when we’re cross, sometimes you don’t want to shout but it just comes out. Let’s have a think together about what might be better for you to do".

All the theories discussed here have one thing in common; they encourage the adult to try to understand the child’s distress. They aren’t about saying ‘don’t worry’ or rushing into ‘fixing’ things.

It can be challenging as an adult to stay calm when a child is not, that’s very human. In those moments Carina’s top tip is to: “Take a deep breath and remind yourself that what you’re seeing is the child's defence mechanism. You might think it’s you, but it’s not. Always go back to the why. Why is the child behaving this way? It may not be easy right now but know that you can help them and you can make a difference”.